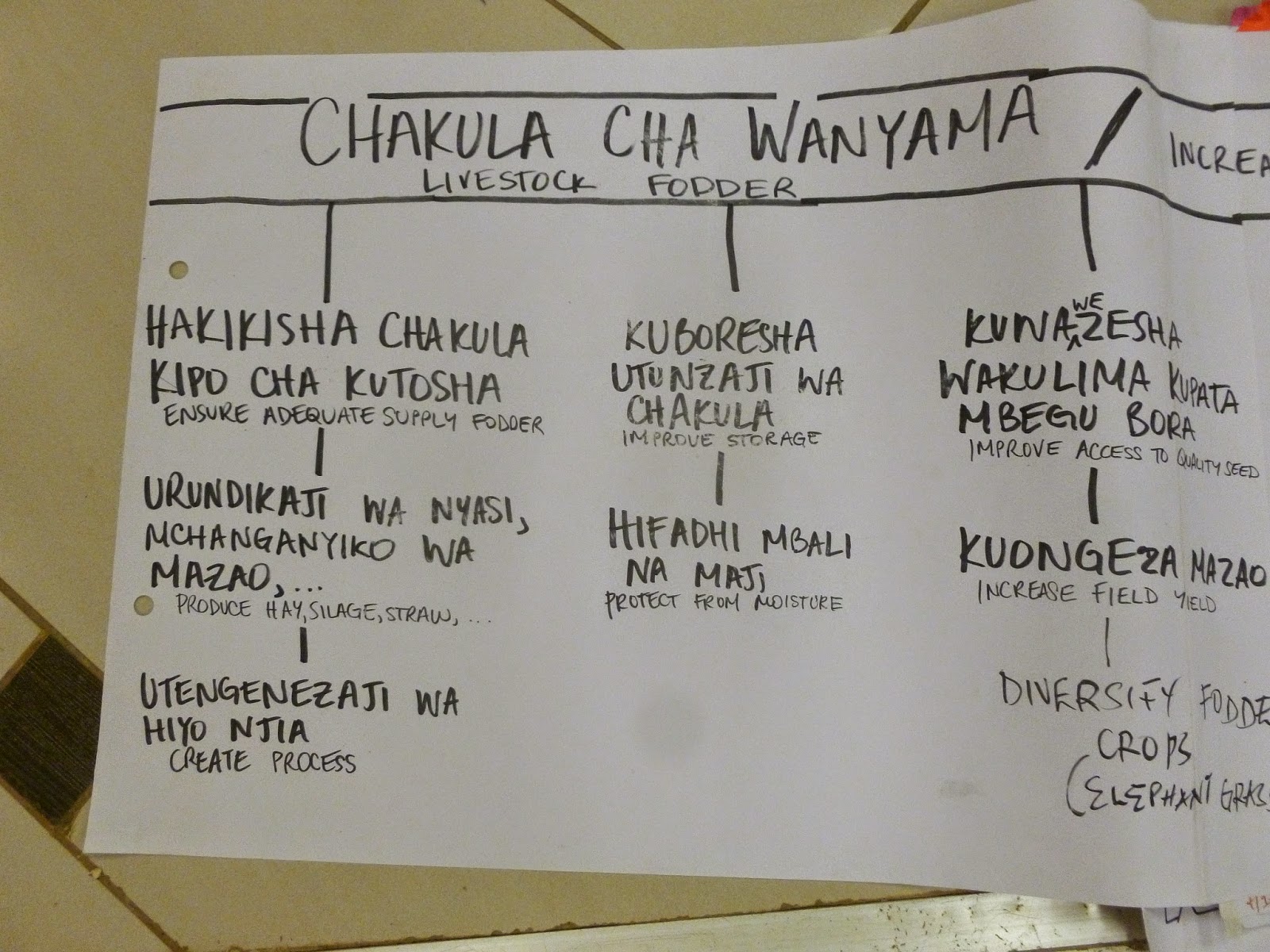

During my team's first community visit to Orkilili, we took every measure to soak up information about the community. Although our primary objective was to gather information about livestock fodder practices, we remained aware of other community events and issues. It was a challenge for my team to meet with farmers individually as community meetings were such an integral part of the culture, however, we did collect a sufficient amount of information. My team was able to generate a problem framing tree.

Just an aside: a problem framing tree is a tool used in design practice to break up large, ambiguous problems into smaller ones which can be chosen and designed for. For instance, my team's 'trunk' was "increase availability of livestock fodder for Maasai." We chose to pursue the branch of "ensure adequate supply of livestock fodder" over branches such as "improve breed selection, or "improving farming education."

As we ideated on the community's major challenges, we saw a larger macro-structure taking shape on the framing tree. Many of our ideas addressed long-term challenges such as education and breed selection and access to quality seed. Nevertheless, we were able to identify other shorter term challenges. However, when we matched our brainstorming ideas with the problem framing statement we realized that our ideas paled in comparison to the large scale challenges. We questioned: how can we design a product for such a specific issue as feeding cattle when such larger issues like how to farm exist?

In 1972 Hoerst Rittel first used the term "wicked" to describe the nature of design problems. Rittel argued that design problems are characterized by high uncertainty. In other words, linear obvious solutions found from analytical approaches are unlikely to successfully resolve design problems such as the one my team and I faced. We faced a wicked problem.

As my team and I argued and discussed our concept conundrum, a quote from a TED Talk popped into my mind. Sami Nerenberg the founder of Design For America posed the poignant question in her TED talk, "What is the smallest change you can make that would have the greatest impact?" At that moment, I lept into the discussion and shared my break through.

It was perfectly acceptable for the team to develop a prototype that only partially addressed the large and unwieldy issue of livestock fodder and prosperity. How could any one product possibly solve all the community's problems?

Following that conversation, my team successfully narrowed our prototypes down. We chose to move forward with a hay baler, a maize stock chopper, and a urea fermentation process.

Just an aside: a problem framing tree is a tool used in design practice to break up large, ambiguous problems into smaller ones which can be chosen and designed for. For instance, my team's 'trunk' was "increase availability of livestock fodder for Maasai." We chose to pursue the branch of "ensure adequate supply of livestock fodder" over branches such as "improve breed selection, or "improving farming education."

As we ideated on the community's major challenges, we saw a larger macro-structure taking shape on the framing tree. Many of our ideas addressed long-term challenges such as education and breed selection and access to quality seed. Nevertheless, we were able to identify other shorter term challenges. However, when we matched our brainstorming ideas with the problem framing statement we realized that our ideas paled in comparison to the large scale challenges. We questioned: how can we design a product for such a specific issue as feeding cattle when such larger issues like how to farm exist?

In 1972 Hoerst Rittel first used the term "wicked" to describe the nature of design problems. Rittel argued that design problems are characterized by high uncertainty. In other words, linear obvious solutions found from analytical approaches are unlikely to successfully resolve design problems such as the one my team and I faced. We faced a wicked problem.

As my team and I argued and discussed our concept conundrum, a quote from a TED Talk popped into my mind. Sami Nerenberg the founder of Design For America posed the poignant question in her TED talk, "What is the smallest change you can make that would have the greatest impact?" At that moment, I lept into the discussion and shared my break through.

It was perfectly acceptable for the team to develop a prototype that only partially addressed the large and unwieldy issue of livestock fodder and prosperity. How could any one product possibly solve all the community's problems?

Following that conversation, my team successfully narrowed our prototypes down. We chose to move forward with a hay baler, a maize stock chopper, and a urea fermentation process.

No comments:

Post a Comment