At many points during the summit, certain design methods which worked when I was designing for farmers in New England did not fit the context of tribal Tanzania.

For instance, it was difficult for my team to gather information in Orkilili. Community members were accustomed to convening large meetings. Men sat in a large circle. Women sat outside the circle and listened. In such settings, my team could only ask questions to the men. However, designers know that only so much insight can be gained from asking questions. Observing users in their environment in addition to trying what users do are equally important. Observing, asking, and trying enable designers to gain deep insight into lives and build empathy.

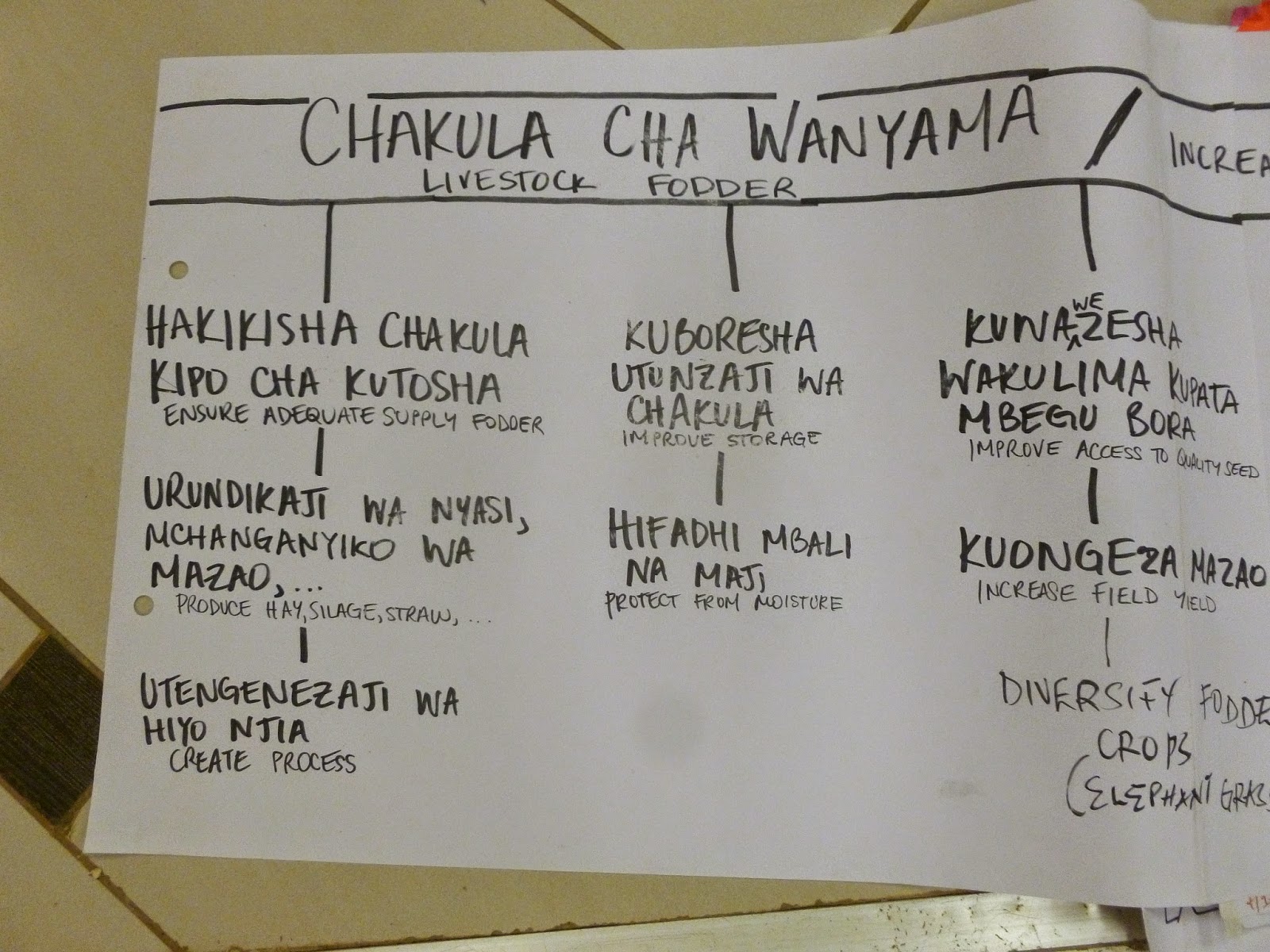

At our first community meeting, we succeeded in gathering information by communicating through images. The industrial designer on my team illustrated the translated responses of community members on topics such as seasons, breeds, and livestock fodder. The drawings seemed to build trust and understanding despite the language barrier.

Our presentation to the community at the end of community visit. We squatted during the community presentation to give community members a greater sense of self-determination and responsibility to provide feedback.

For our community presentation at the end of the first community visit, my team identified strategies to gather feedback effectively in a large community meeting. My team planned to give each attendee a colorful sticker which he

and she would use to vote on the need they felt was important. As my team was assigned to work on livestock fodder production, we wanted community members to vote for three areas of opportunity: fodder storage (preserving what was already there), fodder processing (increasing what was available), and fodder growing (more of a long-term educational project).

As we confidently explained our innovative community strategy, one design facilitator told us that dot voting would not be an appropriate method to engage the community members. Dot voting might disrespect the hierarchy of local leadership. We needed to respect the place of the Mtendagi, or Ward Executive. Despite our enthusiasm for engaging women and men simultaneously, we ended up following a less exciting communication strategy. We intentionally sat during our community presentation to lend power to the community members while sharing our findings with the community using a translated problem-framing tree poster.

The second instance of overcoming intercultural dynamics was during our home stay in the community. As 'guests' of the community it may have been more difficult for the community members to criticize the objects that we created. We may have had a different experience soliciting feedback on prototypes if we had not lived with the Mollel family in Orkilili.

The father of our host family (in bright blue on the left) informally gave us overwhelming positive feedback on our first prototype.